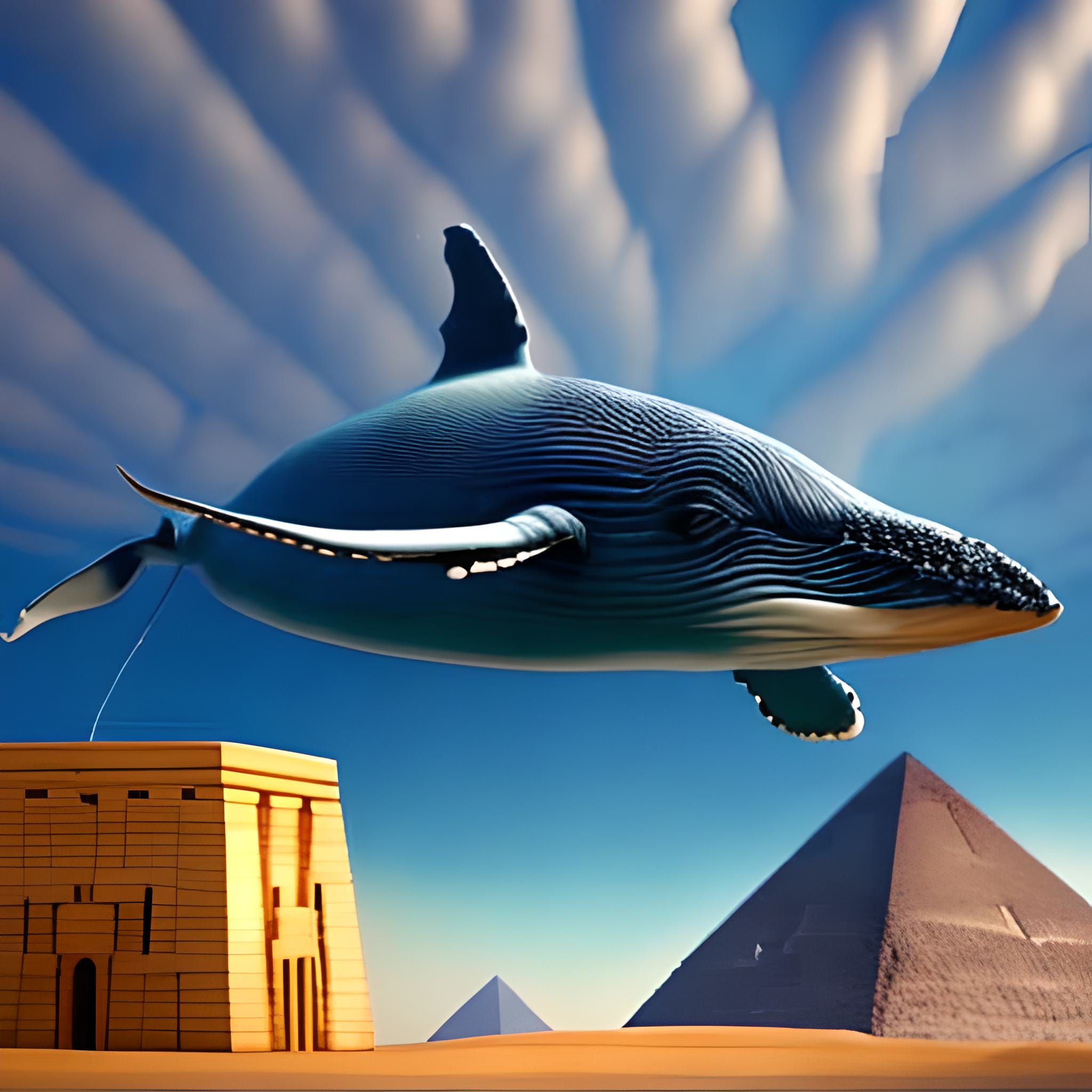

The Ancient Wisdom of the Whales

A true story about sea monsters that scientists thought was only a myth.

The Ancient Greek philosophers, playwrights, and myth-makers lived in a society that had rebuilt itself in the wake of an apocalypse known as the Bronze Age Collapse. Dotted around the landscape were cities built atop the ruins of Mycenaean culture. On innumerable clay tablets were carvings in a script that people could no longer decipher. And in mythology were heroes who could accomplish feats that were no longer possible.

Hesiod told of the prior Gold, Silver, and Bronze Ages of Mankind. Plato invented the myth of Atlantis. It seemed that no matter how much their civilization progressed, scholars and storytellers couldn’t shake the feeling that deep trenches of ancient wisdom and ability had been forever lost.

That feeling remains with us today, mostly in the form of manufactured hoaxes and TV documentaries about ancient aliens building the Pyramids.

It’s all bunk except, every once in a while, when it isn’t. Every once in a while, we learn that a new-to-us nugget of knowledge was common knowledge in ancient times.

For example, it was recently “discovered” that a humpback or Bryde’s whale will sometimes remain perfectly still with its lower jaw perpendicular to the water, allowing fish to swim into its mouth, perhaps attracted by the whale’s regurgitation. When a sufficient number of fish are in the whale’s mouth, its jaws snap closed like a trap. This behavior has been dubbed “trap-fishing.”

Descriptions of similar behavior can be found from Ancient Greek texts up through Old Norse manuscripts but, until the last decade or so, such tales were dismissed as fantasies, optical illusions, or myths.

The mythical aspidochelone, or island-sized “asp turtle,” was described by the Greeks as using this exact hunting tactic. In this case, an Ancient Greek myth may have been based on a true story.

The Norse legend is about a trap-hunting beast called the hafgufa, or “sea mist.” In this case, Medieval sailors—people from a time we call “the Dark Ages”—also knew something that modern science had forgotten.

Two seemingly fanciful stories, separated by millennia of time and a continent of space, may have been based on similar observations. In this case, solid scientific knowledge, rather than being entirely lost, instead passed into a form where it was no longer recognized for what it was.

Ancient and Medieval sailors would have been better able to see uncommon behaviors in whales because there were more of them, back before they were hunted nearly into extinction. Luckily, whale populations have been making a comeback, and new tools, like drones, are expanding our ability to discover these behaviors anew.

But what about the animals that actually did go extinct?

How many so-called myths might hold the key to unlocking the unexpected habits of saber-toothed cats? Or wooly mammoths? Or unicorns? Or any of the other animals that ancient peoples may have ridden to sites where aliens were building megalithic pyramids?

We may never know for sure.

Herland

Updating last week’s Mytho-Crypto, I’ve fallen into a Herland rabbit hole. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 feminist utopian novel was a “lost classic,” generally overlooked until its serialized parts were first collected together for publication in 1979. The story is as fascinating as I remembered but also more incomplete than I ever knew.

Gilman’s original serial publication flowed directly into a lesser-known and more-overlooked sequel, With Her in Ourland. The challenge in publishing Ourland is that has some slower bits that are a slog to get through. It also includes Gilman’s didactic lectures about why eugenics is good actually, among other problematic content.

The Cryptoversal Books solution is to add an abridged selection of Ourland material onto the end of Herland in order to develop the themes, story, characters, and relationships as Gilman intended, toward the conclusion that she intended, without as much of the racism that she intended. With slow-paced and objectionable material left on the cutting-room floor, what’s left of Ourland preserves the best of Gilman being “ahead of her time” while removing the worst of her being “of her time.”

Herland and Ourland, a more-than-complete but less-than-comprehensive Herland, will be the historic first book in the Cryptoversal Bookshelf Collection.

(Sorry Bram Stoker, your time is coming.)

There’s a rumor out there that this will be a print and traditional ebook in addition to a Web3 publication. Let’s talk more about that in the Cryptoversal Discord.

Wordler Co-Authors

I’m one step closer to adding Token-Mediated Co-Author Licenses onto the last batch of NIGHTfall tokens. Our tech partners at MINTangible have signed off on the new collections. Hopefully there will be major news next week.

Year in the Books

Don’t miss your last chance to mint the Year in the Books token before the end-of-March snapshot. I have a feeling that the bonus content this month will be something good.

Have a great weekend. See you next week.

—The Mythoversal Cryptoversal